Santiago, Chile

Summer 2022

I pride myself on being a traveller rather than a tourist. What’s the difference? In my mind, being a traveller means seeking out immersive experiences when I visit a new place, striving to understand what makes the local culture tick. I’m drawn to the uncharted paths, eager to unearth unique facets that offer deeper insights into the places I explore. Of course, I never pass up iconic sites a new city or country has to offer, but my passion lies in discovering those hidden gems that can lead to personal growth. And sometimes, that means we need to confront uncomfortable truths to truly know the places we visit.

During my recent stay in Santiago, I took some time to explore The Museum of Memory and Human Rights (Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos). Established to commemorate and document the human rights abuses that transpired during General Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship from 1973 to 1990, the museum’s primary mission is to educate visitors about this dark chapter in Chilean history and advocate for human rights and social justice. While I had some knowledge of the atrocities under Pinochet’s regime, my visit to the museum opened my eyes to the profound terror that Chileans endured during that period and the ongoing healing process.

Historical Context

Pinochet’s regime seized power in 1973 through a military coup, aiming to establish authoritarian control and reshape Chilean society. Their agenda involved dismantling leftist political and social groups, eliminating perceived threats, and implementing neoliberal economic policies. This transformation occurred alongside widespread human rights abuses, including torture, disappearances, and political repression. Simultaneously, they embraced free-market capitalism and privatized state-owned industries, attempting to overhaul the Chilean economy.

The exact death toll from human rights abuses during Pinochet’s regime varies. The Rettig Report of 1991 documented 2,279 cases of killings or disappearances, while the later Valech Report identified over 30,000 victims of human rights abuses, including torture and imprisonment. Many cases remain unaccounted for, leaving the true extent of the abuse shrouded in uncertainty.

The Museum’s Inauguration

The Museum of Memory and Human Rights officially opened its doors to the public on January 11, 2010, under the leadership of then-Chilean President Michelle Bachelet. She played a crucial role in the museum’s establishment and had herself been a victim of human rights abuses during the Pinochet dictatorship. Her presidency marked an era of increased emphasis on human rights and historical memory in Chile.

Architecture

The museum’s architectural design by Mário Figueroa is both distinctive and symbolic. As I approached the courtyard, the angular façade caught my attention, symbolizing the fragmented and turbulent nature of Chilean society during the dictatorship. The irregular, zigzagging exterior mirrors the chaos and division that defined the era. What struck me was the exterior’s reflective material, serving as a metaphor for self-examination. Inside, the intentionally labyrinth-like layout left me disoriented, echoing the confusion and uncertainty experienced by the victims of human rights abuses.

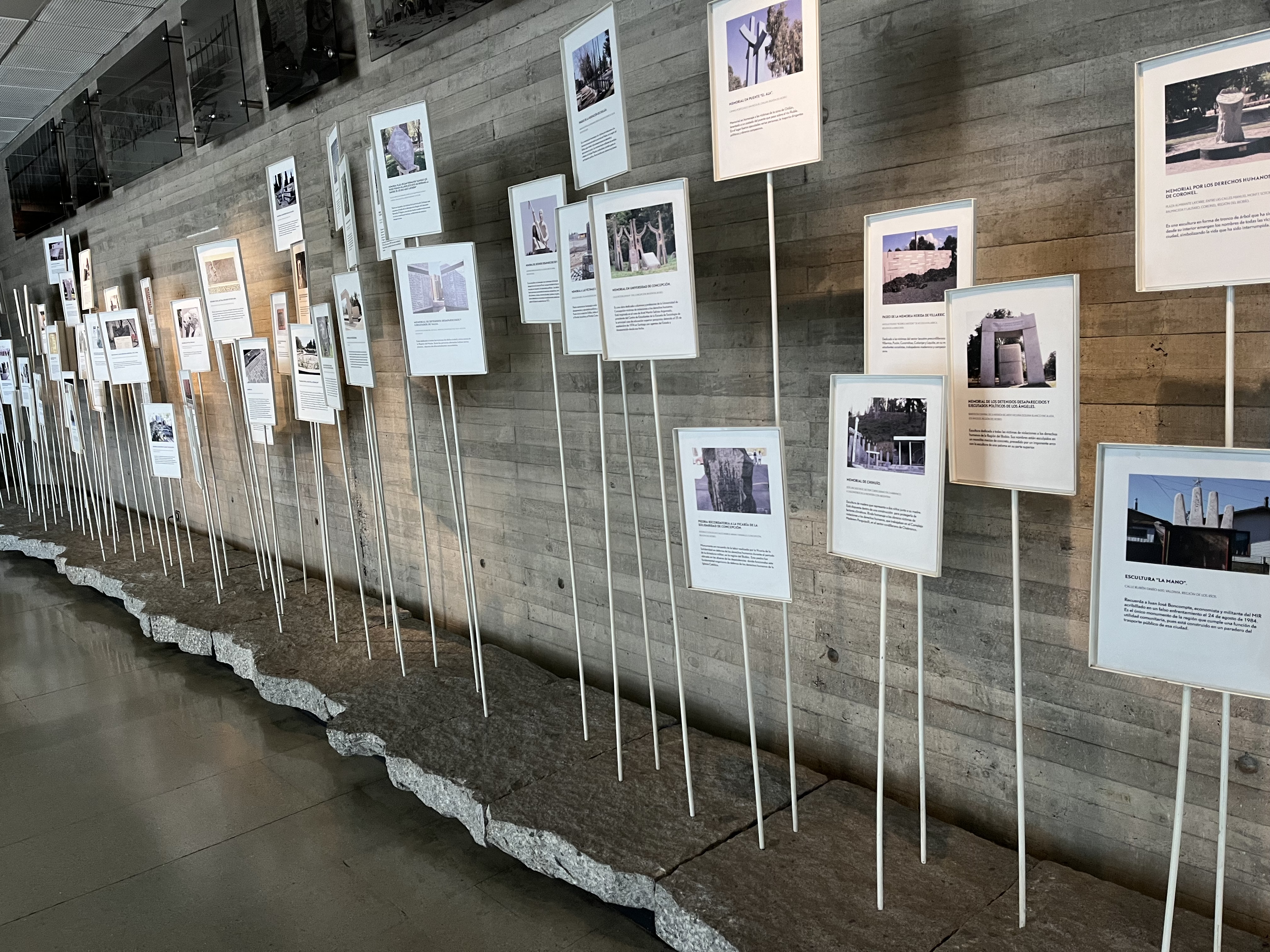

Permanent Exhibition

The permanent exhibition is a comprehensive and emotionally charged display. It combines artefacts, documents, and personal stories presented through traditional displays and immersive experiences. I was not only educated by the historical documents but profoundly moved by the immersive experiences.

One of the most impactful sections involves the documented stories of survivors, victims’ families, and activists. These oral histories, often accompanied by photographs, videos, and written accounts, humanize the atrocities and enable visitors to connect on a deeply personal level with those affected. Although I felt the connection to the victims, survivors, and their families as recounted here, it was unfathomable to me to understand those people who organized and participated in the “death flights” or “disappearance flights”, where individuals detained by the military were taken aboard planes, drugged or physically restrained, and then thrown out of the aircraft over the ocean. This was truly horrific.

What also deeply unsettled me was the treatment of children during the Pinochet regime. Although the exact number of children who were murdered or disappeared hovers around 300, precise figures remain elusive. The museum’s detailed exploration of how children were impacted by political repression, violence, and upheaval during that period was both eye-opening and heart-wrenching. Many children lost one or both parents to forced disappearances. Some pregnant women detained during the dictatorship gave birth in captivity, and their children faced unimaginable challenges, often separated from their mothers. Families fleeing persecution often included children, and the trauma of that era continues to cast its shadow over these individuals and their families.

The Wall of Portraits and Reflection Area

Within the museum, two elements stand out as powerful reminders of the human rights abuses under Pinochet. The massive wall of portraits showcases black and white images of victims, spanning two stories. These portraits are not just photographs; they are powerful representations of the diverse individuals – men, women, and children – who suffered during the regime. As I examined each frame, some simply portraying a blank black or white canvas due to an absence of available photographs, I couldn’t help but wonder about each person and the ordeals they surely endured.

Adjacent to the portraits is a tranquil reflection area. Surrounded by illuminated shards of glass resembling candles, this space invites quiet contemplation while overlooking the wall of portraits. Candles, symbols of light, hope, and remembrance, serve as a poignant reminder of the imperative pursuit of justice and human rights. Here, I spent time reflecting on the exhibits, the museum itself, and the people who endured such grievous abuse. I also thought about the many amazing and welcoming people I encountered over my time in Chile, and how they and their families might have been impacted during the Pinochet regime.

These exhibits and testimonials, combined with the overall architecture of the museum, are intentionally designed to evoke powerful emotions, and encourage visitors to engage with the exhibits on a personal and emotional level. They remind us of the individuals who suffered during the dictatorship and underscore the museum’s mission to preserve their memory while advocating for human rights and social justice.

Outside the museum, the Forest of Chairs is a poignant and symbolic art installation. Empty chairs represent victims of human rights abuses, symbolizing the void left by these individuals and their continuing absence from seats of power.

Reconciliation and Healing

The museum plays a pivotal role in Chile’s ongoing process of reconciliation, healing, and national unity after the horrors of the Pinochet dictatorship. It offers a safe and respectful space for victims and their families to share their stories and experiences, ensuring that their voices are heard. The museum actively supports the pursuit of justice for human rights violations through collaborations with human rights organizations, legal institutions, and advocacy groups – both locally and internationally. For many survivors, it provides a place for healing and closure, validating their experiences.

The museum’s broader contribution is to foster national unity in Chile by preserving the memory of human rights abuses and championing human rights. It underscores the importance of acknowledging the past to build a more just and unified Chile.

Final Thoughts

Understanding a place’s history, including its dark chapters, is vital for any traveler. While I savour discovering new experiences, enjoying local cuisines, and uncovering those hidden gems, I also believe that acknowledging a destinations difficult history is a crucial part of the journey. Confronting uncomfortable truths about the places we visit enables us to delve deeper into the essence of those locations. I’m a blend of that traveller and tourist – a seeker of diverse experiences and an embracer of understanding a destination’s full story.

In concluding my visit to The Museum of Memory and Human Rights, I left with a profound sense of the importance of bearing witness to history, confronting uncomfortable truths, and advocating for human rights. My journey as a traveler continues, fueled by the belief that understanding the past is integral to shaping a better future – both for the places we explore and for ourselves.

Leave a comment